Lua C Module Tutorial

This tutorial walks through a minimal but practical example of a Lua C Module for fsmapper.

Using the rotation sample included in the Plugin SDK, you will learn how a native Lua C module emits fsmapper events from background threads, how those events carry structured data, and how a Lua script consumes and reacts to them at runtime.

The focus of this tutorial is not on detailed API reference documentation, but on understanding how fsmapper, Lua, and native code work together in a real Lua C module implementation.

What this sample demonstrates

This sample demonstrates how to extend fsmapper using a Lua C Module, rather than a Custom Device Plugin.

It consists of two main parts:

- A Lua C module (

rotation.dll) that emits fsmapper events from native code - A Lua script (

testscript.lua) that visualizes those events and interacts with the module

The module implements a virtual rotation model similar to the Custom Device Plugin example. It periodically generates two-dimensional coordinates representing a point moving along a circular path. Unlike the device plugin version, the Lua C module packs both the X and Y coordinates into a single event value.

On the Lua side, the script receives these composite event values and uses them to animate a small yellow circle moving inside a semi-transparent blue rectangle located at the upper-left area of the screen.

The script also provides user interaction through a semi-transparent rectangular area. Each tap toggles the rotation state or direction, and the control command is sent back to the module.

From the user’s point of view, this sample demonstrates:

- Emitting fsmapper events directly from a Lua C module

- Passing structured data (X and Y coordinates) as a single event value

- Visualizing module-generated events in real time

- Bidirectional interaction between Lua and native code

Although this sample implements behavior similar to the Custom Device Plugin tutorial, it highlights the increased flexibility available when using a Lua C module.

The complete source code for this sample (rotation.cpp and testscript.lua) is included in the Plugin SDK under the samples directory.

For convenience, the same code is also available on GitHub and can be viewed directly in your browser:

-

How to build and run

This sample is included in the fsmapper Plugin SDK under the following directory:sdk\samples\lua_c_modules\rotationThe Visual Studio solution in this directory builds a Lua C module named

rotation.dll. -

Build requirements

To build the sample, Visual Studio must be installed with the following workloads enabled:- C++ desktop development

- Universal Windows Platform development

-

Building the module

You can build the module either from Visual Studio or from the command line usingmsbuild.msbuild rotation.sln /p:Configuration=Release /p:Platform=x64This produces

rotation.dllunder thex64\Releaseoutput directory. -

Running the sample

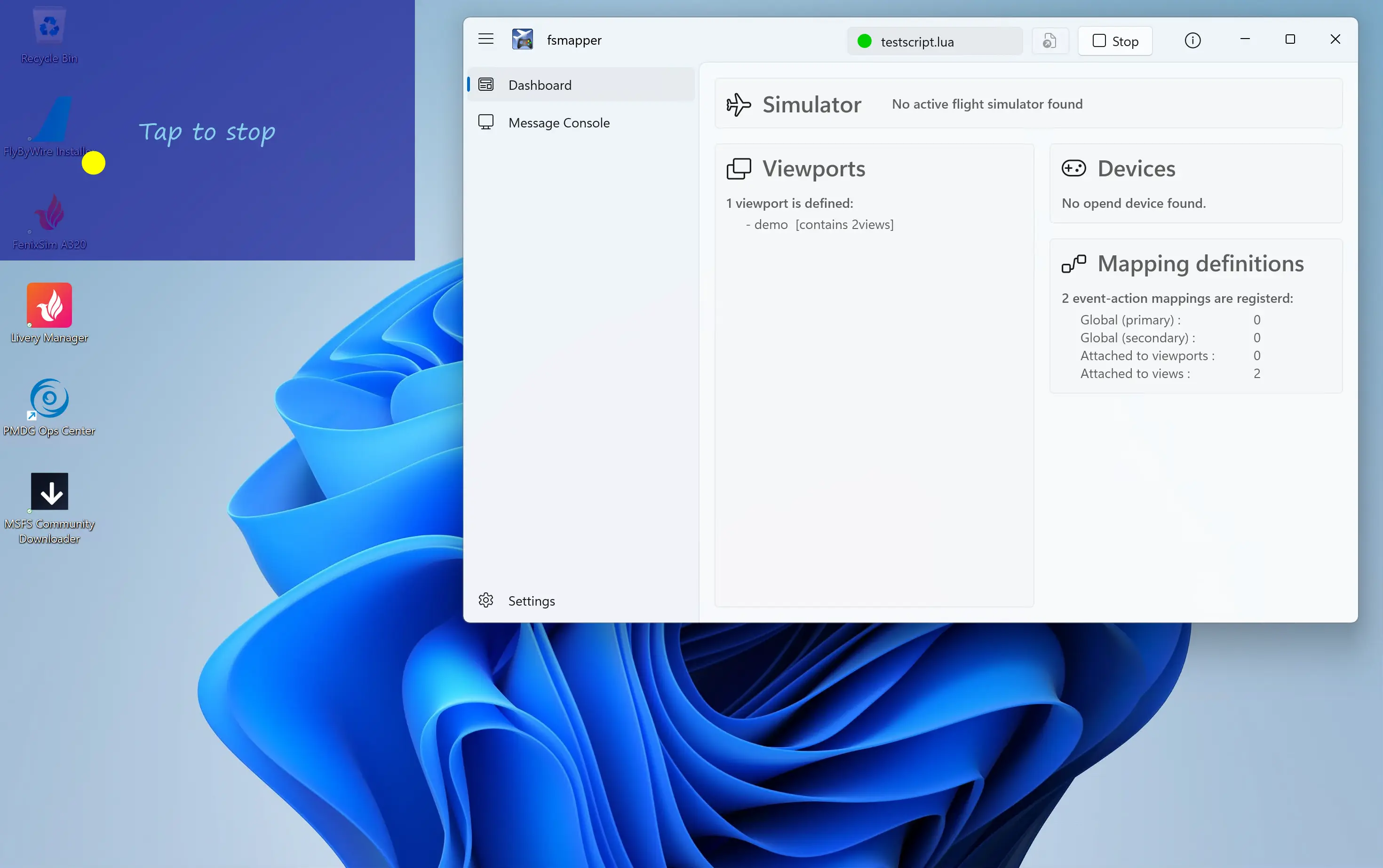

No manual installation or file copying is required.The accompanying Lua script (

testscript.lua) explicitly adds the build output directory topackage.cpath, allowing Lua to loadrotation.dlldirectly from the build location.To run the sample:

- Launch fsmapper

- Execute

testscript.lua

The Lua script will load the module, start emitting rotation events, and display the animated visualization immediately.

Getting started

Before looking at the module implementation, let’s briefly review the basic setup required to build a Lua C module for fsmapper.

Lua version and execution environment

fsmapper embeds Lua 5.4 and executes Lua scripts within its own Lua runtime environment. Therefore, Lua C modules for fsmapper must comply with the Lua 5.4 C API.

Required header files

To implement a Lua C module, you typically include:

- Standard Lua C API headers

- fsmapper’s Lua C module service API header

The fsmapper Plugin SDK provides the above all necessary header files under the sdk\include directory.

When using C++, Lua headers must be included with extern "C" to avoid name mangling issues.

extern "C" {

#include <lua.h>

#include <lauxlib.h>

}

#include <mapperplugin_luac.h>

The mapperplugin_luac.h header declares the service APIs that allow Lua C modules to:

- Emit fsmapper events asynchronously

- Write messages to the fsmapper console

- Manage module-specific service contexts

Linking against fsmapper

fsmapper statically embeds Lua internally, so Lua C modules must not link against any external Lua library.

Instead, both the Lua C API symbols and the fsmapper service APIs are provided by fsmappercore.dll.

To link correctly, specify fsmappercore.lib from the SDK’s sdk\lib directory.

Using a pragma directive is a convenient and commonly used approach:

#pragma comment(lib, "fsmappercore.lib")

This linkage ensures that the module is dynamically bound to fsmapper’s runtime environment at load time.

Exposing the module to Lua

A Lua C module is loaded from Lua using require().

When require('rotation') is executed, Lua loads rotation.dll and calls the module entry point function named luaopen_rotation.

local rotation = require('rotation')

In this sample, the module entry point is implemented as follows:

extern "C" __declspec(dllexport) int luaopen_rotation(lua_State* L){

static const luaL_Reg module_funcs[] = {

{"emitter", emitter::create_emitter},

{nullptr, nullptr},

};

luaL_newlib(L, module_funcs);

return 1;

}

In the Lua C API, data is exchanged between Lua and native code through a Lua stack managed by lua_State.

Functions exposed to Lua are responsible for pushing their return values onto this stack and reporting how many values they return.

In this entry point, luaL_newlib creates a new Lua table, populates it with the functions defined in module_funcs, and pushes that table onto the Lua stack.

The return value 1 tells Lua that the function returns exactly one value—the table that becomes the result of require('rotation').

As a result, this entry point returns a Lua table containing the module’s public API.

In this sample, the module exports the emitter function, making it available from Lua as rotation.emitter(...).

local emitter = rotation.emitter(event_id, rpm, side_length)

This sample does not require copying rotation.dll into a global module search path.

Instead, the Lua script extends package.cpath to include the build output directory, allowing require('rotation') to load the DLL directly from the build location.

package.cpath = package.cpath .. ';' .. mapper.script_dir .. 'x64/Release/?.dll' ..

';' .. mapper.script_dir .. 'x64/Debug/?.dll'

local rotation = require('rotation')

With the module loaded and its API table available, the next step is creating an emitter object and starting it.

Creating an emitter object

The primary API exposed by this module is the rotation.emitter(...) function.

From Lua, this function creates an emitter object that represents a native rotation model and returns it as a Lua value.

local emitter = rotation.emitter(event_id, rpm, side_length)

On the native side, rotation.emitter is implemented by the Lua C function emitter::create_emitter.

This function acts as a bridge between Lua and native code, translating Lua-level arguments into native objects and returning a Lua representation of those objects.

static int emitter::create_emitter(lua_State* L){

// Check arguments

FSMAPPER_EVENT_ID event_id = luaL_checkinteger(L, 1);

double rpm = luaL_checknumber(L, 2);

double side_length = luaL_checknumber(L, 3);

// Create emitter object

auto fsmapper = fsmapper_luac_open_ctx(L, userdata_name);

emitters.emplace_back(fsmapper, event_id, rpm, side_length);

auto object_ref = std::prev(emitters.end());

object_ref->self = object_ref;

// Create Lua user data that holds a reference to the emitter object

auto udata_ptr = lua_newuserdatauv(L, sizeof(emitter_ref), 1);

auto udata = lua_gettop(L);

new(udata_ptr) emitter_ref(object_ref);

// Register the metatable for Lua user data (only on the first call)

if (luaL_newmetatable(L, userdata_name)){

auto meta_table = lua_gettop(L);

// Set __gc field

lua_pushcfunction(L, gc);

lua_setfield(L, meta_table, "__gc");

// Set __index field

static const luaL_Reg methods[] = {

{"start_cw", start_cw},

{"start_ccw", start_ccw},

{"stop", stop},

{nullptr, nullptr},

};

lua_newtable(L);

luaL_setfuncs(L, methods, 0);

lua_setfield(L, meta_table, "__index");

}

// Set metatable into new user data

lua_setmetatable(L, udata);

// Create asynchronous event source and register event provider function

// that will be called in the Lua scripting thread

object_ref->async_source = fsmapper_luac_create_async_source(

fsmapper, L, event_provider, udata

);

// Retern one value, note that the stack top is a user object

// that reference to the emitter object

return 1;

}

Retrieving arguments from the Lua stack

In the Lua C API, function arguments are passed via the Lua stack.

The first argument is located at stack index 1, the second at index 2, and so on.

In this sample, the arguments are retrieved using the following Lua auxiliary library functions:

luaL_checkintegerfunction retrieves the specified argument as an integerluaL_checknumberfunction retrieves the specified argument as a floating point number

If any argument is missing or has an incompatible type, these functions raise a Lua error automatically.

The meaning of the arguments in this sample is:

event_id

An fsmapper event ID that has been registered on the Lua side and passed into the module.rpm

The rotation speed, expressed in revolutions per minute.side_length

The length of one side of a square that bounds the circular motion.

The emitter computes X and Y coordinates within this square and emits them as event values.

Creating and storing the native emitter object

The emitter objects are owned and managed entirely on the native side.

They are stored in a static std::list, which allows stable storage and predictable lifetime management.

When a new emitter is created:

- A new

emitterinstance is constructed and appended to the list - An iterator (

std::list<emitter>::iterator) pointing to that list element is stored inside the object itself

This design ensures that Lua never owns the emitter object directly. Instead, Lua holds a reference that can be used to control the object while native code retains full ownership.

Representing the emitter in Lua using userdata

To expose the emitter object to Lua, the function creates a userdata value using lua_newuserdatauv.

This userdata holds a small native structure (emitter_ref) that references the corresponding emitter object as std::list<emitter>::iterator.

Userdata is Lua’s mechanism for representing user-defined native types. Unlike tables, userdata has no inherent behavior, but behavior can be attached through a metatable.

In this sample:

- The

__indexfield of the metatable is populated with methods such asstart_cw,start_ccw, andstop - This allows Lua code to call methods in an object-oriented style:

Lua

emitter:start_cw() - The

__gcfield is set to a native function that releases resources when Lua’s garbage collector collects the userdata

The metatable is registered using luaL_newmetatable.

This function creates the metatable only once per lua_State; on subsequent calls, the existing metatable is reused.

As a result, the metatable setup cost is paid only on the first emitter creation.

Preparing for asynchronous event emission

At the end of emitter::create_emitter, the function calls fsmapper_luac_create_async_source.

This registers an asynchronous event source that allows the emitter’s worker thread to signal event emission safely.

The details of how asynchronous event sources work, and how the event_provider function is invoked from the Lua scripting thread, are covered in a later section.

Implementing the emitter

The emitter object represents the native implementation of the rotating motion model. Its primary role is to run independently of the Lua scripting thread and periodically notify fsmapper that a new event should be emitted.

In this sample, that behavior is implemented entirely inside the emitter’s constructor, where a worker thread is launched.

emitter::emitter(FSMAPPER_LUAC_CTX fsmapper, FSMAPPER_EVENT_ID event_id, double rpm, double side_length)

: fsmapper(fsmapper),

event_id(event_id),

rpm(rpm),

radius(side_length / 2.){

worker = std::thread([this]{

std::unique_lock lock{mutex};

while (true){

if (direction == mode::stop){

cv.wait(lock);

}else{

cv.wait_for(lock, std::chrono::milliseconds(50));

}

if (should_be_stopped){

break;

}

if (direction != mode::stop){

// Notify fsmapper that an asynchronous event has occurred.

// The actual event ID and event value are provided later

// when event_provider() is invoked on the Lua scripting thread.

fsmapper_luac_async_source_signal(async_source);

}

}

});

}

The worker thread is started immediately when the emitter object is constructed. It runs in a loop that waits on a condition variable and wakes up periodically while the emitter is active.

The important points here are:

- The worker thread never interacts with Lua directly

- Its only responsibility is to determine when an event should occur

- When it detects that an event should be emitted, it calls

fsmapper_luac_async_source_signalfunction

fsmapper_luac_async_source_signal function is thread-safe and may be called from any thread.

It does not emit an fsmapper event immediately.

Instead, it tells fsmapper that an asynchronous event is pending.

The actual event ID and event value are supplied later, when fsmapper invokes the associated event provider function on the Lua scripting thread. This mechanism allows complex or structured Lua values to be generated safely, without violating Lua’s threading constraints.

Event provider semantics

An asynchronous event source bridges worker threads and the Lua scripting thread by deferring event generation to a Lua C function called an event provider.

In this sample, the asynchronous event source is created inside the emitter constructor via

fsmapper_luac_create_async_source.

At that time, two pieces of information are registered together:

- The event provider function (

event_provider) - A Lua object passed as the provider argument (the emitter userdata)

When the worker thread later signals the asynchronous event source, fsmapper invokes the registered event provider on the Lua scripting thread, passing the same Lua object as its argument. This allows the event provider to safely access Lua values while still reacting to asynchronous activity originating from native code.

The event provider is responsible for producing the actual event payload. It must return the event ID and event value using the Lua C API calling convention, by pushing values onto the Lua stack and returning the number of results.

Event provider implementation

static int event_provider(lua_State* L){

auto udata = reinterpret_cast<emitter_ref*>(luaL_checkudata(L, 1, userdata_name));

auto& self = *udata->operator ->();

std::lock_guard lock{self.mutex};

// update angle and calculate coordinates

auto now = clock::now();

auto dt = std::chrono::duration_cast<std::chrono::milliseconds>(now - self.prev_time).count() / 60000.;

self.angle += (self.direction == mode::cw ? 1. : -1) * 2. * std::numbers::pi * self.rpm * dt;

auto x = std::cos(self.angle) * self.radius + self.radius;

auto y = std::sin(self.angle) * self.radius + self.radius;

self.prev_time = now;

// Return event-id and 2-dimensional coordinates as a table:

// return event_id, {x=x, y=y}

lua_pushinteger(L, self.event_id);

lua_newtable(L);

auto rtable = lua_gettop(L);

lua_pushnumber(L, x);

lua_setfield(L, rtable, "x");

lua_pushnumber(L, y);

lua_setfield(L, rtable, "y");

return 2;

}

This function is invoked with the Lua object specified when the asynchronous event source was created.

In this sample, that argument is a Lua userdata that holds a reference to the underlying emitter instance

(specifically, a std::list<emitter>::iterator), so the event provider receives it as the first argument

(stack index 1).

The function begins by validating and retrieving the userdata using luaL_checkudata function.

This ensures that the passed object is the expected userdata type associated with userdata_name.

Once the native emitter instance is obtained, the function locks self.mutex to safely access and update shared state.

This is important because the worker thread and the event provider can both touch emitter state.

Returning an event using the Lua stack

In the Lua C API, return values are passed back to Lua by pushing them onto the Lua stack.

In this sample:

lua_pushinteger(L, self.event_id)pushes the event IDlua_newtable(L)creates a Lua table and pushes it- The fields

xandyare stored into the table usinglua_setfield

Finally, return 2 tells Lua (and fsmapper) that two values are returned:

- The event ID

- The event value (a Lua table

{x=..., y=...})

fsmapper interprets this (event_id, value) pair and emits the event accordingly, allowing Lua scripts to handle the event using normal event-action mappings.

In the next section, we will look at how the Lua script registers the event ID and how it consumes the {x, y} table value to drive the visualization.

Interacting with the module from Lua

This section highlights the key interaction points between the Lua script (testscript.lua) and the rotation Lua C module.

Rather than explaining the entire script line by line, it focuses on how fsmapper concepts—events, views, and actions—are used together with a Lua C module.

Loading the Lua C module and creating an emitter

The Lua script first adjusts package.cpath so that Lua can locate the compiled module, then loads it using require:

package.cpath = package.cpath .. ';' .. mapper.script_dir .. 'x64/Release/?.dll' ..

';' .. mapper.script_dir .. 'x64/Debug/?.dll'

local rotation = require('rotation')

The script registers an event ID and creates an emitter object by calling the module’s factory function:

local change_coordinates = mapper.register_event('change coordinates')

local emitter = rotation.emitter(change_coordinates, rpm, m_radius * 2)

emitter:start_cw()

Here:

change_coordinatesis an event ID registered on the Lua siderpmcontrols the rotation speedside_length(m_radius * 2) defines the size of the square bounding the circular motion

The emitter object returned to Lua is a userdata value that represents a native emitter instance implemented in C++.

Receiving structured event values

Unlike the Custom Device Plugin example, this Lua C module emits a single event whose value is a table containing both coordinates:

{ x = ..., y = ... }

This allows the Lua script to handle the X and Y coordinates together as one logical update.

In the sample script, the event mapping directly applies this table to the canvas:

{event=change_coordinates, action=canvas:value_setter()},

The built-in value_setter() action assigns the event value to canvas.value, triggering a redraw.

This keeps the Lua code concise and avoids managing multiple independent coordinate events.

Visualizing the coordinates with a canvas

A canvas view element is used to visualize the (x, y) coordinates produced by the emitter:

local canvas = mapper.view_elements.canvas{

logical_width = canvas_size,

logical_height = canvas_size,

value = {x = 0, y = 0},

renderer = function (ctx, value)

ctx.brush = circle_color;

ctx:fill_geometry{

geometry = circle,

x = value.x, y = value.y,

}

// ... drawing code other than circle ...

end

}

The renderer function reads the structured value and draws a small circle at the corresponding position.

Whenever canvas.value is updated by an event, the visualization is refreshed automatically.

Controlling the emitter from Lua

The emitter userdata also exposes a small control API to Lua:

emitter:start_cw()

emitter:start_ccw()

emitter:stop()

These methods are implemented in the Lua C module and update the native emitter’s internal state. From the Lua script’s perspective, the emitter behaves like a regular object with methods, while the actual motion logic and threading remain entirely on the native side.

In the sample, these methods are invoked in response to user interaction:

{event=tap, action=function ()

if is_moving == 1 then

is_moving = 0

emitter:stop()

else

is_moving = 1

direction = direction * -1

if direction > 0 then

emitter:start_cw()

else

emitter:start_ccw()

end

end

canvas:refresh()

end},

Summary

From the Lua script’s perspective, the Lua C module provides:

- A single event carrying structured

{x, y}coordinate data - A simple object-oriented control interface via userdata methods

- Clean separation between visualization logic in Lua and motion logic in native code

Compared to the Custom Device Plugin approach, this model offers greater flexibility in how event data is structured and produced. In addition to emitting richer, structured values, a Lua C module can offload more complex computation or state management into native code, beyond the constraints of device units and scalar values.

While Custom Device Plugins are highly optimized for fsmapper’s device and event–action mapping model, Lua C modules provide a broader design space when more expressive data exchange or advanced native-side logic is required.

Next steps

In this tutorial, you saw how a Lua C module can extend fsmapper by implementing native functionality, emit events asynchronously, and interact with Lua scripts using structured data and userdata-based APIs.

From here, you can explore the Plugin SDK Reference for Lua C Modules to learn more about:

- The Lua C module service APIs provided by fsmapper

- Thread-safe logging and event emission from native code

- Asynchronous event sources and event provider semantics

These references provide the detailed specifications needed to design more advanced Lua C modules, offload complex processing to native code, and build richer integrations beyond this sample.